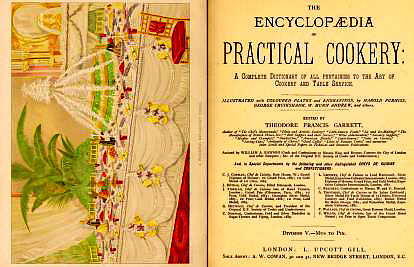

|